By: Akos Balogh

A terrorist attack has hit the western world and taken the lives of over 50 innocent people. We can’t help but feel shocked and dismayed at this atrocity.

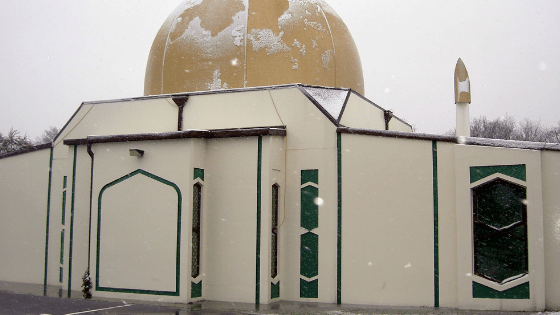

This time it was peaceful New Zealand that bore the brunt of the horror. But contrary to what many have come to expect when hearing about a terror attack, it wasn’t ISIS inspired terrorists who did the murdering. Instead, it was a white supremacist who attacked peaceful Muslim worshipers, as they went about their Friday prayers.

How do we respond to an event like this?

Words escape us, even as we reach for the most negative adjectives we can muster: ‘shocking’, ‘grotesque’, ‘disgusting’ – our vocabulary is strained trying to define it, let alone make sense of it.

And yet, as the initial shock slowly wears off, we can’t help but try and process it, and – as far as possible – understand it.

Like so many others, I’ve found the the days following to be emotionally difficult. But as I process this tragedy, here are 10 thoughts that come to mind:

1. The Secular Mind Is Increasingly Limited In Its Understanding of Terrorism

The only way it knows how to make sense of terrorism is to medicalise it.

Secular people are as shocked by terrorism as religious people. We all struggle to find words that make sense of it. But as we look at how the secular authorities – whether journalists, or state authorities – are describing this issue, notable is the struggle – at times even reluctance – to define it in overtly moral categories.

The New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern described these events as ‘an act of extraordinary and unprecedented violence’, and ‘act of extreme violence’.

Yes, the PM clearly condemns the terrorist act. But describing it as ‘violent’ stops short of condemning it in overtly moral terms. Missing is the use of the term ‘evil’.

Journalists, too, seemed reluctant to use overtly moral terms. Words like ‘’grotesque’, ‘horrific’, ‘cold-blooded’, came close to moral condemnation (and arguably include moral meaning). But it wasn’t long before terms like ‘working class madman’ appeared, suggesting that there had to be mental illness involved. (Although the conservative The Australian led with the headline ‘An Evil Aussie Export’, and journalist Greg Sheridan – a conservative Roman Catholic – described it as ‘an act of pure evil’).

And so, to the secular mind something this awful could only have been caused by someone who had a medical problem. Nothing else quite explains why people are driven to act in this ‘violent’ way.

Such reporting should not surprise us. The post-modern secular mind has discarded overtly moral categories like ‘evil’ – even as it strains toward moral terms to describe this tragedy. In the secular worldview, there is no objective standard of good and evil, standing above time and culture. In this view, different cultures and different people have different moral standards. And so, who are we to judge which moral standard is inherently better than any other?

And yet, making terrorism a mental health issues rarely makes sense of it.

Sometimes – if not often – those who commit such criminal acts are in their right mind. They act rationally – even as their underlying beliefs are warped. As secular Canadian philosopher John Ralston Saul points out, when discussing an even greater act of racist violence:

“It is hard…to avoid noticing that the murder of six million Jews was a perfectly rational act…[But] we carefully assign blame for [such] crimes to the irrational impulse.” [1]

We simply assume that the Nazis – and now neo-Nazis – had some kind of mental illness leading them to act irrationally and murder people. But the overwhelming majority of Nazis were not psychologically disturbed, or acting ‘irrationally’ (as if they suffered from mass-psychosis). They acted in their right minds – psychologically speaking. However, those minds were deficient: not medically deficient, but morally deficient.

Yes, we may find out that the terrorist, Brenton Tarrant, has serious psychological issues. But from what we know, he didn’t have a history of it. As his former boss said, ‘He was a very dedicated personal trainer…He worked in our program that offered free training to kids in the community, and he was very passionate about that.’

Only the moral category of ‘evil’ makes sense of Tarrant’s actions.

2. These Events Shatter The Myth of Human Control of the world

We like to think we’re in control of our world. But we’re not.

Modern Westerners like to think we’re the masters of our world. And over the last 150 years, we’ve done a lot to shape the world so that we feel secure and comfortable. Modern medicine, food technology, economic growth – all these have delivered a world of comfort and ease unimaginable to people even 100 years ago. And so, we delude ourselves into thinking life is under our control.

But it’s not. Sure, we can have enormous influence over our world – but we don’t control it. Control over our world is not something given to us.

And there’s nothing like a terrorist event out of the blue – in our backyard, no less – to rudely awaken us to our lack of control.

3. The Unintended Consequences of Social Media

Zuckerberg et.al. promised it would bring the world closer together. But it hasn’t.

We must be careful not to blame social media for terrorism. But it’s increasingly hard to deny that it plays a role in helping radicalise terrorists. And yet, that was never the aim of social media.

In 2009, Mark Zuckerberg declared:

“[As people share their lives online], the world will become more open, and people will have a better understanding of all that is going on around them.”

But few people would agree with him today. As journalist Nancy Gibbs pointed out:

“Facebook’s business model is echo-chamber construction. Its beams and struts are algorithms that favour news that will connect with us, ideas that affirm our own. Civil discourse suffers both from the echo, which amplifies even small, sordid sounds, and the chamber, which walls us off from diverse opinions, from ideas that might disturb us in healthy ways.”

Overall, social media hasn’t brought us together: its pulled us apart, making us a more polarised society. We’re increasingly ready to judge those who disagree with us, and social media algorithms happily show stories on our newsfeed that fuel our outrage.

Furthermore, the internet – and social media in particular – allows for the sharing of ideas, including evil ones. These ideas fuelled the warped worldview of this gunman – and of other groups like Islamic State. Journalist Greg Sheridan writes:

“You get attention on the net by being more extreme, more emotional, more foul-mouthed, than the next fellow. Everyone involved in politics and online activism should reflect on the dangers of exaggerated rhetoric, exaggerated grievance, exaggerated resentment.”

I’m not blaming Zuckerberg and Silicon Valley for terrorism. But their technology does shape us – even in unintended and pernicious ways.

4. Blaming This Act On Political Grievance Is Irresponsible

Grievance alone (over political/social issues) does not a terrorist make.

While the blood was still fresh in the mosques of Christchurch, Australian Senator Fraser Anning made this notorious statement:

“The real cause of bloodshed on New Zealand streets today is the immigration program which allowed Muslim fanatics to migrate to New Zealand in the first place.”

Anning’s logic is very simple:

Some people are upset by the increased Muslim presence in their society, and this will lead these people to act violently against Muslims. In other words, grievance over a political/social issue leads to violence.

(It should be noted we also saw this ‘grievance = terrorism’ argument from some Australian Islamic leaders after the Paris terror attacks).

But there are many problems with Anning’s logic.

For starters, millions of people are aggrieved over political or social issues all the time (e.g. after the election of Donald Trump), yet they are not drawn to violence. For violence to be an option – especially such horrific violence – something more than mere grievance is required.

It requires an (evil) worldview that justifies terror. And it’s that evil worldview which we need to condemn. Sadly, Anning did not condemn it. Grievance alone does not a terrorist make.

5. The Sharp Tension Between Freedom, and Security

You can have freedom, or you can have security. But you can’t have both – at least not to the same degree.

Our police and security services do a valiant job. They work hard to protect us from evil – and more often than not, they succeed.

But let’s face it: their job would be so much easier if we lived in a surveillance state (like China). If all our data, our private phone calls, even our public movements were tracked, then the government could do a better job of preventing terrorist acts. Of course, we lose our freedom if our government went down that Orwellian path – leading to other, greater problems.

And so, we’re left with this dilemma: remain free, but with reduced security; or lose more of our freedom, and gain greater ‘security’.

But considering totalitarian regimes in the 20th century oppressed and killed more people than all the terrorist acts of the last 100 years, I say we keep our freedom. And manage the terrorist threat as best we can.

6. The Understandable (Knee Jerk) Reaction Will Be to clamp Down on ‘Hate Speech’

But the problem is: who gets to define ‘hate speech’?

Soon after the shooting, the UK’s Guardian had an opinion piece from a British Muslim lady, Masuma Rahim, who said the following:

“These days we have racists and extremists on mainstream television all the time, and hardly anyone in any position of influence bats an eyelid…They dress it up as “free speech”, but through their actions hatred has been legitimised…”

While there is understandable emotion in her words, she gets to another dilemma facing free societies: how much freedom should we give people in their speech?

There will be increasing calls to clamp down on ‘hate speech’ – particular speech that is perceived to belittle or attack minorities such as Muslims. Indeed, I noticed that American right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos was banned from Australia after making remarks about the Christchurch attack (you can read his remarks here).

But who gets to define what ‘hate speech’ is? When it comes to Islamophobia (an obvious motivation in this particular terrorist attack) the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), a 57-country alliance based in Saudi Arabia, has long campaigned for a global blasphemy law as protection from a broadly defined “Islamophobia”. Should the OIC’s standard be our standard for acceptable speech?

Not only is hate speech difficult to define – one person’s hate speech is another person’s truth telling – but it again gives the state greater power over what we can and can’t say.

Now we Christians are called to ‘give no [unnecessary] offence to Jews or Greeks’ so that we might share the gospel with them and see them saved (1 Cor 10:32 – 11:1). We can’t support ‘hateful’ speech. But here’s the problem: classical Christian teaching is increasingly seen as hateful speech. Whether it’s declaring that Jesus is Lord (and thus Mohamed is a false prophet); or that homosexual practice is sinful, Biblical teaching could easily fall afoul of hate speech laws.

Which is why Christians should be cautious about giving government more power to regulate speech, even as we ensure that our speech is respectful and loving.

7. Identity Politics is Pulling Society Apart

And is now found on both the right, and the left.

Journalist Greg Sheridan makes a salient point when he writes:

“[W]estern society has taken a terrible wrong turn by going down the road of identity politics. If the organising principle of politics and even social organisation is identity, that leads to appalling, unnecessary and gravely dangerous division.”

He continues:

“In the United States, minority identity politics has produced a backlash of white identity politics. Everyone wants to be a victim. Everyone craves the psychological reassurance of racial group identity and phony solidarity”.

Many argue that Trump was elected in part as a white working class backlash against identity politics. But here in Australia, identity politics is leaving the campus, and slowly going mainstream, not just on the Left, but now on the far right as well. And the logical end point of such identity politics is violence against those who are seen to threaten our identity.

It’s all quite ominous. So how should Christians respond?

8. Christians Should Not be Optimists or Pessimists About Our World’s Future

We should be hope-filled realists.

As a Christian, I am neither optimistic, nor pessimistic about the future.

Rather, I am hopeful.

Hopeful, confident, that one day evil will be punished; wrongs will be righted; and peace will rule the earth forever. And so I do not fear; I do not despair; rather, I depend on the Resurrected King, Jesus Christ, to take care of me, and one day bring His people home to His new world. A world in which there is no death, or hate: where even nature itself is at peace:

“Righteousness will be his belt and faithfulness the sash around his waist. The wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard will lie down with the goat, the calf and the lion and the yearling together; and a little child will lead them. The cow will feed with the bear, their young will lie down together, and the lion will eat straw like the ox.”

“The infant will play near the hole of the cobra, and the young child put his hand into the viper’s nest. They will neither harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain, for the earth will be full of the knowledge of the LORD as the waters cover the sea.”

– Isaiah 11:5-9

9. The Christian Opportunity: Building Bridges with Those Who Are Different

Christians must not see others as ‘The repugnant cultural other’.

The Project host Waleed Aly gave an impassioned statement in response to the attack:

“For [me], I’m going to say the same thing I said about four years ago after a horrific Islamist attack. Now, now we come together. Now we understand that this is not a game, terrorism doesn’t choose its victims selectively, that we are one community and that everything we say to try to tear people apart, demonise particular groups, set them against each other, that all has consequences even if we’re not the ones with our fingers on the trigger.”

Whether or not you agree with all of Aly’s views, he makes an important point. As a society, we’re better off if we come together, than remain in our own echo-chambers.

We’re better off if we personally know those we disagree with, rather than see them as repugnant ‘others’ on social or mainstream media.

We’re better off if we can empathise with our opponents, rather than impute to them every evil motive under the sun.

And Christians have a golden opportunity to shine like stars in this broken society of ours. We have the emotional and spiritual resources to reach out to those who are different, to those we avoid, even to those who hate us.

Now is the time to do just that. When people are afraid, when people are anxious, we can bring comfort and hope.

10. The Christian Obligation: Making Disciples of all Nations

Regardless of their political or religious views.

While we can and must reach out to our neighbours in love (whoever they might be), we need to do more.

While our society will do whatever it can to stop this from happening again – monitor social media more closely, ban violent video games, put more people on a police watch list – only the gospel can turn a person from evil, to good. Only the gospel has the power to move a person from dangerous radicalism, to Christ-centred radicalism: a radicalism that loves their neighbour, rather than destroys them.

That’s the gospel we’re called to preach.

Those are the people we’re called to be.

Those are the disciples we’re called to make.

[1] John Ralston Saul, Voltaire’s Bastards – The Dictatorship of Reason in the West (Victoria: Penguin Books, 1992), 16.

Article supplied with thanks to Akos Balogh.

About the Author: Akos is the Executive Director of the Gospel Coalition Australia. He has a Masters in Theology and is a trained Combat and Aerospace Engineer.